Caleb learned early that hunger was negotiable.

He didn’t remember ever being truly starving—just uncomfortable enough to complain. Meals appeared on the table like clockwork, regardless of whether he liked them. That consistency bred a certain confidence. Food, to him, was something that adjusted to him.

When he didn’t like what was served, he said so.

“I don’t like onions,” he’d announce, pushing the plate away with two fingers like it was contaminated.

His mother would pause. Look at him. Then quietly take the plate and scrape it clean into the trash.

No yelling. No lectures.

Just the sound of food hitting plastic.

It unsettled him at first. Most of his friends’ parents argued, pleaded, bargained. His mother didn’t do any of that. She simply removed the meal and went about her evening.

If he was hungry later, he found cereal in the cupboard.

That was the arrangement.

As he grew older, his opinions sharpened.

At ten, he declared soup “lazy food.”

At thirteen, he accused her of “not understanding flavors.”

At sixteen, he critiqued textures, temperatures, seasoning levels with the seriousness of a judge on a cooking show.

She listened.

Always listened.

Sometimes she nodded.

Sometimes she smiled faintly, as if committing something to memory.

Caleb mistook that silence for defeat.

By the time he moved out, he’d refined his palate enough to be insufferable.

He returned home rarely—holidays mostly—and when he did, he treated the meals like performances he’d paid for. His mother cooked anyway. Roasts. Stews. Baked goods that filled the house with warmth and memory.

He picked them apart.

“This is overdone.”

“This tastes rushed.”

“You didn’t let this rest long enough.”

Family dinners became tense, then short, then infrequent.

His father eventually stopped inviting him.

Years passed.

Caleb built a life that required little patience. Microwave dinners. Takeout. Restaurants where mistakes were comped and apologies plentiful. He married briefly. Divorced quickly.

When his father died, he returned home out of obligation more than grief.

The house felt smaller. Quieter. Too clean.

His mother had aged in subtle ways—hands thinner, hair lighter—but her posture was unchanged. Upright. Attentive.

“I made something,” she said when he arrived. “I wasn’t sure how long you’d stay.”

He sighed. “You didn’t have to.”

“I wanted to.”

The table was set for one.

The meal was… fine.

Perfectly edible. Nothing remarkable. Nothing offensive.

He still found fault.

“This needs salt,” he said, reaching for the shaker.

Her hand stopped him mid-motion.

“Try it first,” she said gently.

He rolled his eyes but complied.

Chewed. Swallowed.

“Yeah,” he said. “Salt.”

She nodded. Sat down across from him. Didn’t eat.

That should have bothered him.

It didn’t.

He stayed the night.

The guest room smelled faintly of lemon cleaner and something else—something metallic, maybe. He slept poorly.

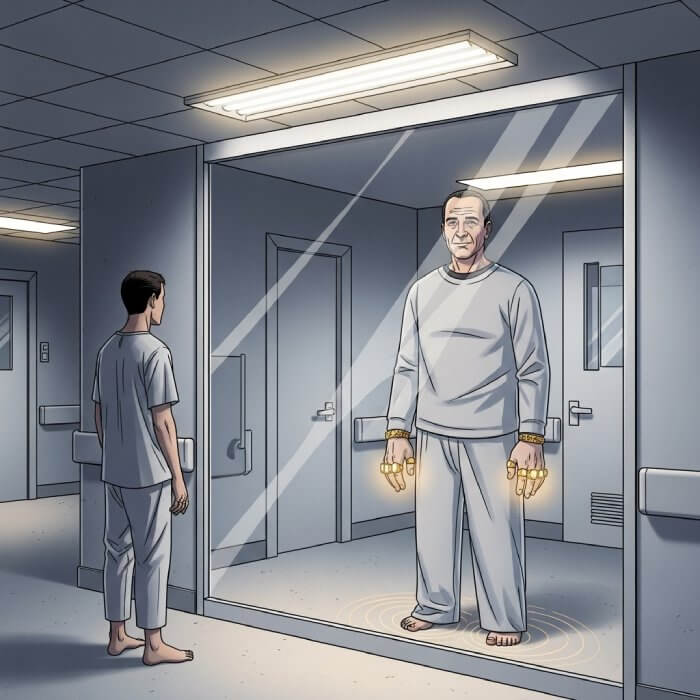

When he woke, he was sitting at the dining table.

That was the first thing he noticed.

The second was the weight around his wrists.

Zip ties. Tight. Cutting off circulation.

Panic surged, immediate and hot.

“Mom?” he croaked.

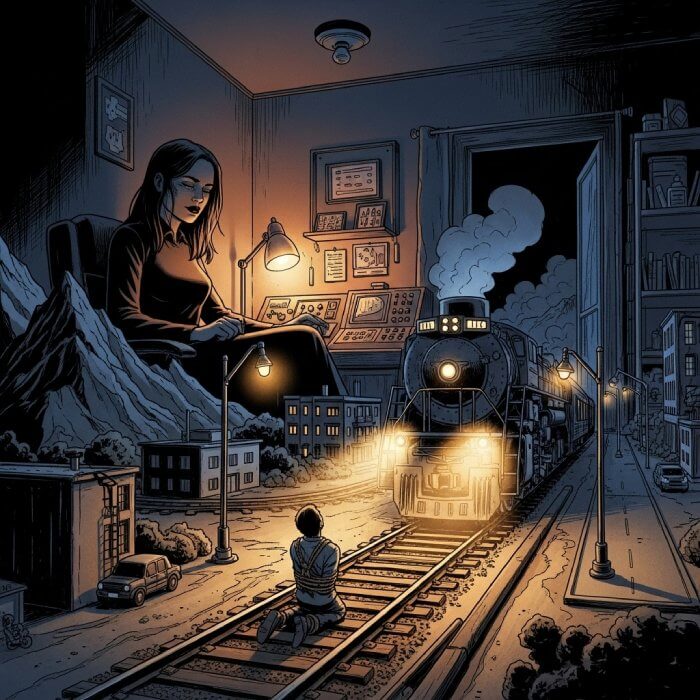

She stood at the stove, back to him, stirring something slowly.

“Good morning,” she said.

“Untie me. What the hell is this?”

She turned.

In her hands was a ladle. On the counter beside her: a series of covered dishes, arranged neatly, like courses.

“You’re hungry,” she said.

“No,” he snapped. “I’m scared.”

She considered that.

“Hunger feels like fear sometimes.”

She set a plate in front of him.

It was familiar. Something she’d made often when he was young.

He stared at it.

“I’m not eating that.”

She didn’t respond.

He pulled against the ties. The chair creaked.

“You’ve lost your mind,” he said. “I’ll call the police. I swear to God—”

She lifted something from beneath the table.

A heavy object. Black. Cold.

She rested it gently on her lap.

Caleb went silent.

“You’ll eat,” she said. “Then we’ll talk.”

The first bites were forced.

Gagged down between shallow breaths and rising terror. She watched every chew. Every swallow.

When he finished the plate, he slumped back, chest heaving.

“Good,” she said, collecting the dish.

Relief washed through him—until she placed another plate down.

“This one too.”

His voice cracked. “I did what you wanted.”

“You did what you always do,” she replied. “You judged it. You endured it. You didn’t appreciate it.”

“I said thank you!”

She smiled faintly.

“No. You consumed.”

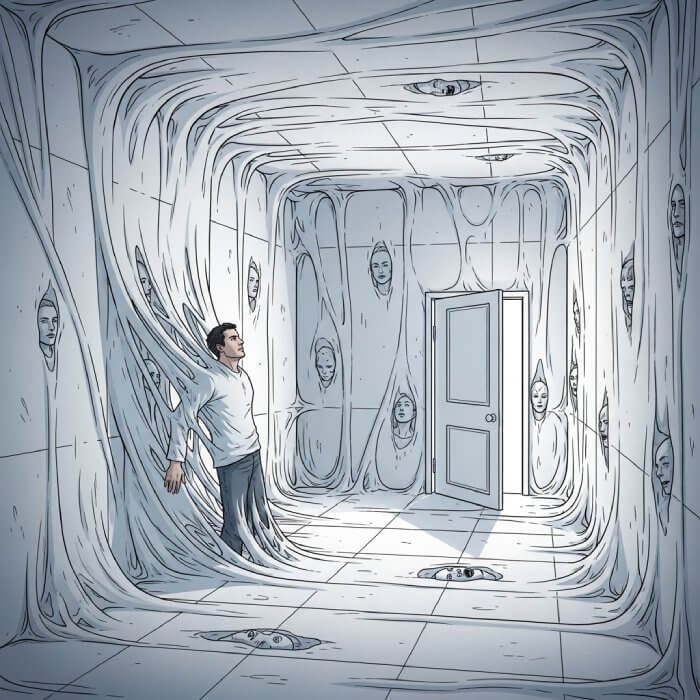

Course after course followed.

Foods from his childhood. Dishes he’d insulted. Meals he’d rejected.

His stomach bloated painfully. His throat burned. He vomited once and was made to eat that plate again, cleaner this time.

Between bites, she spoke.

“You don’t know what it’s like,” she said calmly, “to feed someone who never wants what you make. To pour effort into something just to watch it be dismantled with words.”

He cried. Apologized. Promised to change.

She nodded, as if acknowledging weather.

When the final plate came, it was empty.

He sobbed in relief.

She slid it toward him anyway.

“Finish,” she said.

“There’s nothing on it,” he whispered.

She tilted her head.

“Isn’t there?”

The plate was ceramic. Thick. White.

He shook his head violently. “No. No, please.”

She raised the object in her lap just enough to remind him.

Hands trembling, he lifted the plate.

Bit down.

The sound was unbearable.

Pain exploded across his mouth. Blood filled his throat. He screamed, shards cutting gums, tongue, cheeks.

He chewed because stopping hurt more.

Swallowed because choking would be worse.

When it was over, he collapsed forward, sobbing wetly.

She reached out.

Stroked his hair.

“There,” she said softly. “Now you know.”

They found him days later.

Seated at the table. Chair overturned. Mouth ruined.

The plates were gone.

So was she.

In the kitchen sink, soaking in soapy water, was a single note written neatly on a recipe card:

He finally finished his meal.

I think he liked it.